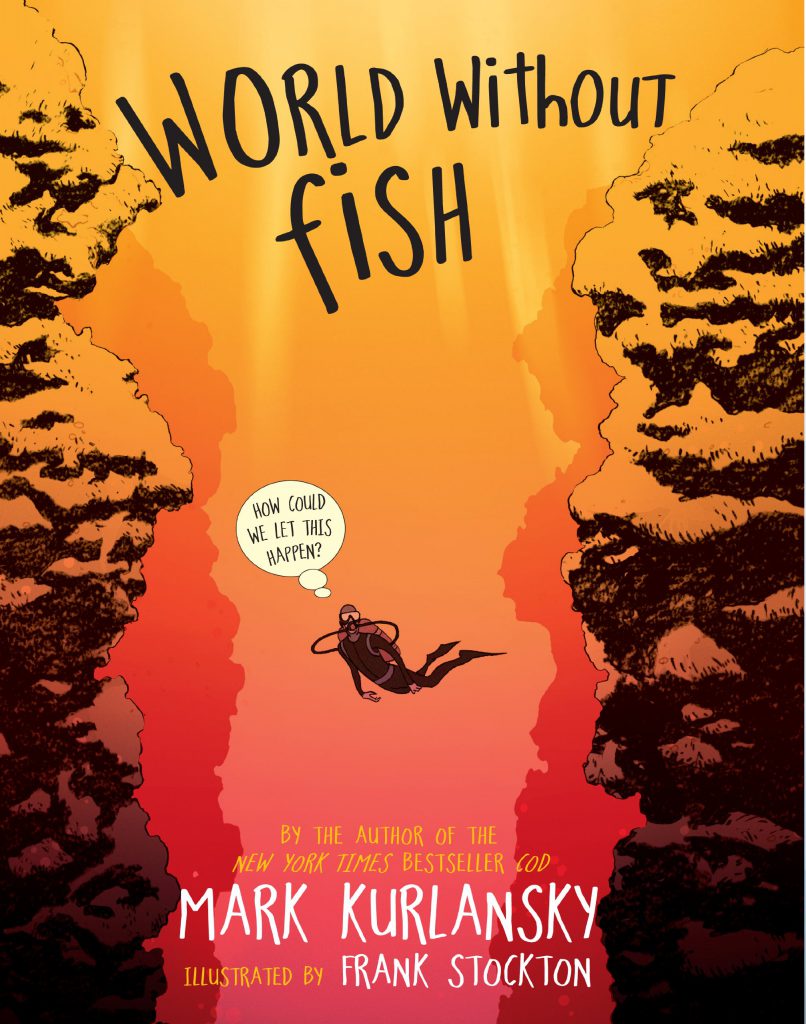

“Most stories about the destruction of the planet involve a villain with an evil plot. But this is the story of how the Earth could be destroyed by well-meaning people who fail to solve a problem simply because their calculations are wrong” — World Without Fish, p. x.

| Creator(s) | Mark Kurlansky (writer), Frank Stockton (illustrator) |

| Publisher | Workman Publishing Company |

| Publication Date | 2014 |

| Genre | Educational, Nonfiction |

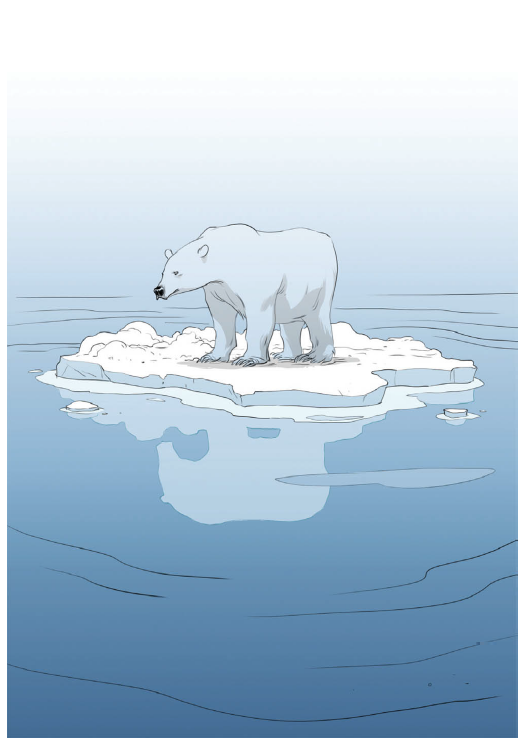

| Environmental Themes and Issues | Endangered Species, Extinction, Overfishing, Pollution, Plastics, Climate Change, Ocean Conservation, Algal Blooms, Tourism, Coral Reef Bleaching, Sustainable Living, Environmental Activism, Oil Spills, Melting Ice Caps, Educational Nature Facts |

| Protagonist’s Identity | Ailat: White female protagonist The non-comics portions of the book have an omniscient narrator |

| Protagonist’s Level of Environmental Agency | Level 5: High Environmental Agency and Activism |

| Target Audience | Middle Grade (8 to 12 years) |

| Settings | Ocean |

Environmental Themes

“Most of the fish we commonly eat, most of the fish we know, could be gone in the next fifty years,” Mark Kurlansky writes in the opening chapter of World without Fish (xi). This dire tone pervades the rest of the text as Kurlansky describes the many pressing environmental issues threatening our oceans, ranging from climate change to overfishing to pollution. The dense book provides a detailed history of the fishing industry, covering the cultural, industrial, and political factors that have contributed to overfishing and the threatened extinction of many fish species. For instance, one chapter spotlights the tragic story of the orange roughy, which was overfished into extinction in the 1990s only two decades after humans discovered the species.

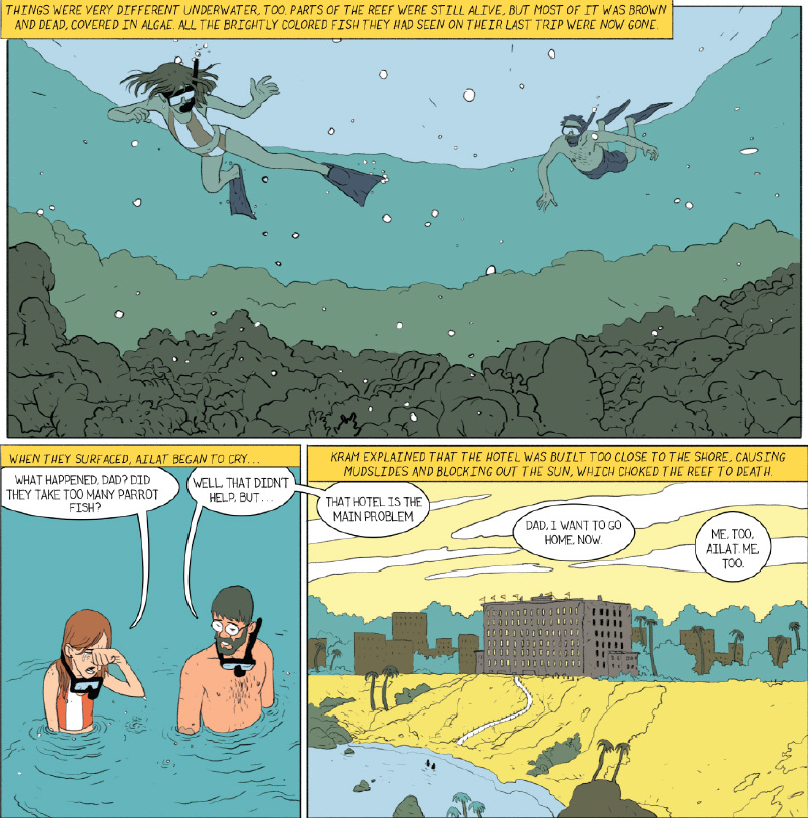

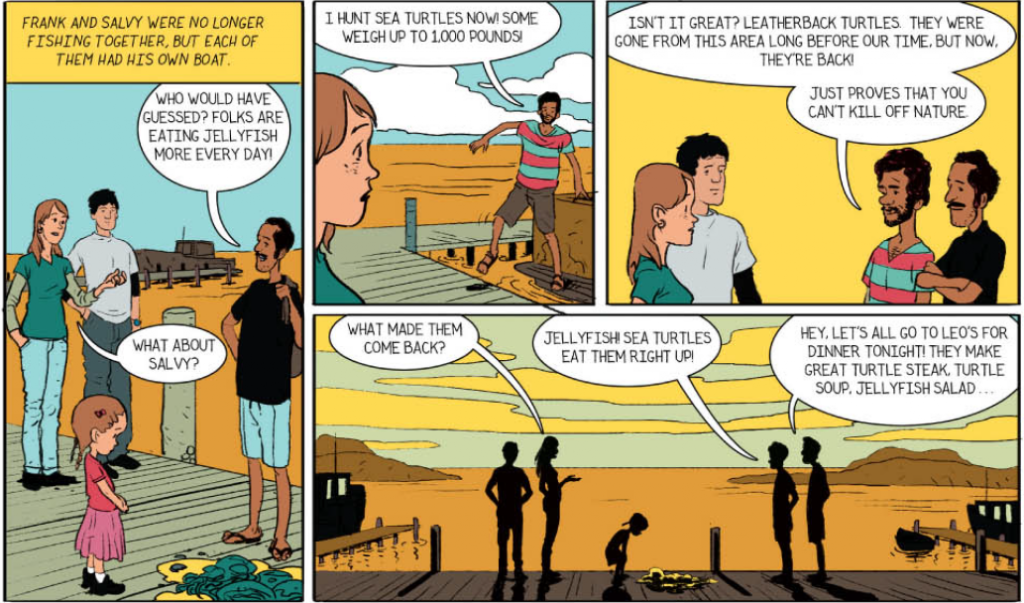

In between each of the book’s eleven chapters, Kurlansky and illustrator Frank Stockton insert one page installments of the comic “The Story of Kram and Ailat.” This fictional comic centers on marine biologist professor Kram and his young daughter Ailat, whose names playfully reverse the first names of author Mark and his daughter Talia. In the comic’s opening pages, Kram and Ailat go fishing together, as well as visit Kram’s commercial fishermen friends, Frank and Salvy. All of the characters catch plentiful fish, though Kram warns his friends that they are taking too many fish. As the comic progresses and Ailat grows older, however, the characters witness the slow destruction of ocean ecosystems. By Part 5 of the comic, bottom fish, seabirds, crabs, and whales have vanished from the ocean. In Part 6, a hotel built too close to the ocean shore has killed the coral reef where Kram and Ailat snorkel. In Part 7, Frank and Salvy have resorted to harvesting hag fish, or “slime eels,” from the empty oceans, and Kram and Ailat witness a red tide. By Part 8, only krill remain in the ocean, and, in Part 10, an adult Ailat is alarmed to find that environmental destruction now affects the land, resulting in the disappearance of birds and insects. Finally, in Part 11, the comic concludes as Ailat’s own daughter asks, “Mommy, what’s a fish?” (142). Together, these comic strips provide a frightening vision of a potential future where the environmental issues detailed in the book have wiped out most of the life in the ocean and on the land.

Despite the book’s troubling examination of the perils of overfishing and other environmental threats, Kurlansky–a former fisherman himself–doesn’t offer a blanket condemnation of the actions of all fishermen. Instead, he describes conflicts between fishermen and scientists, arguing that both have made mistaken judgements about ocean ecosystems at different times and neither should be consider wholly correct about how to regulate fishing. Moreover, Kurlansky argues that fishing should continue in a more sustainable way rather than stopping altogether. He writes, “It would seem that the simplest and surest solution to helping fish repopulate the oceans would be just stop all fishing. After all, a complete end to fishing would remove a constant and important predator from the food chain. But while it might save the fish in the short term, we can’t predict what the environmental impact of suddenly removing a major predator from the ocean would do to the Earth’s natural order” (Kurlansky 77). He suggests ways that the fishing industry can harvest wild fish more sustainably, such as limiting the amount of time that individual fishermen can fish instead of setting rigid quotas and closing off areas to allow fish to repopulate.

The book also highlights other issues contributing to shrinking marine life populations, including climate change, plastic pollution, oil spills, and poisonous metals that have leaked into oceans. The primary narrative concludes by listing ways that readers can help to address the problem, including avoiding inexpensive fish that may have been caught in an unsustainable way, selecting fish that have been labeled as “Certifiable Sustainable Seafood” by the Marine Stewardship Council, and avoiding particularly threatened species of fish, such as sharks and bluefin tuna. Additionally, Kurlansky encourages children to engage in direct forms of environmental activism by organizing a picket line, writing letters to elected officials, and joining environmental groups. In the final lines of the primary narrative, he appeals directly to the child reader, writing, “[Y]ours is a special generation, one faced with more responsibilities and more opportunities than any generation in history. You cannot afford to be passive. You have to learn about what is happening to the planet and you will have to act” (Kurlansky 171).

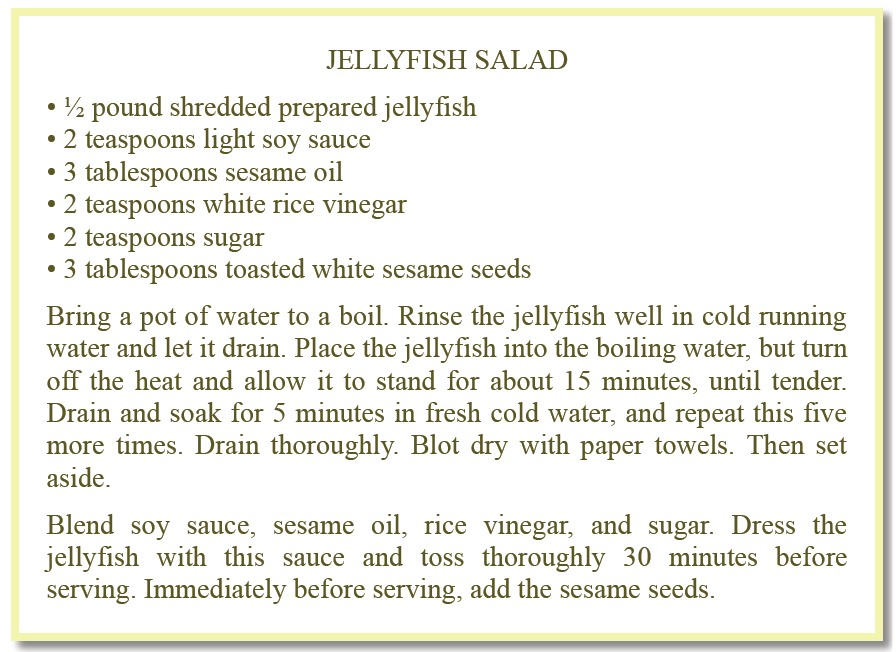

In addition to the comic, World without Fish includes a variety of different textual and visual components, presumably partially in an attempt to maintain the attention of young readers. The majority of the text consists of textual narration. Kurlansky prints most of the text in small, black font, but he also emphasizes key statements by writing them in large, all-capitalized blue and red fonts. Accompanying this text, Stockton includes vivid, brightly colored illustrations of different fish and undersea habitats. Other visual components include realistic drawings of different fish species, each captioned with facts about the creatures, charts, photographs, maps, and even a recipe for “jellyfish salad.” Finally, quotes from Charles Darwin appear at the beginning of each chapter.

Paratexts

World Without Fish includes several useful paratexts that educate the implied middle-grade reader about ways that they can help to combat the environmental issues detailed in the primary narrative. A section entitled “Resources: Environmental Groups Working on Marine Issues” lists eleven prominent non-profit institutions currently involved in ocean conservation efforts, including the Blue Ocean Institute, the Environmental Defense Fund, and the Ocean Alliance. Kurlansky includes a paragraph describing each organization’s history and goals, as well as urls to their websites.

Additionally, the paratext includes a copy of the Seafood Watch pocket guide from July 2010. The guide divides fish species available for consumption into “Best Choices,” “Good Alternatives,” and types to avoid. Kurlansky urges readers to find the most updated version of the list to use while purchasing fish from restaurants and supermarkets. Finally, the paratext features three numbered lists that teach children about different aspects of becoming an environmental activist. “Nine Steps Toward Building a Movement” encourages children to form environmental coalitions, focus on small, local actions like making posters, and opening new chapters of their organizations in different schools. “Seven Useful Traits of a Movement Organizer” identifies personality traits that children should cultivate to become a movement organizer, including creativity, empathy, idealism, and studiousness. Finally, “Five Things You Can Do to Save the Oceans and the Fish” includes five tangible steps that children can undertake to help the oceans, including reducing their plastic consumption, educating their families about sustainable fisheries, and writing to government officials to express concerns about climate change, pollution, and other environmental issues.